“There is nothing in the intellect that was not first in the senses, except the intellect itself. Human intellectual powers need material to work upon. This comes from nature through the senses. Nature provides the materials, and the human intellect conceives and constructs the works of civilization which harness nature and increase its value and its services to the human race.”

The Trivium, Sister Miriam Joseph, C. S. C. Ph. D., Page 22.

|

Term |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

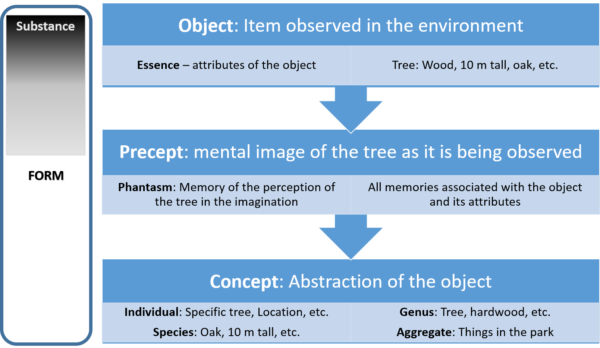

Object |

The item in nature or the environment that is perceived by a person. This is a single instance of a given thing – a chair, tree, desk, etc. It will have to have substance to be perceived by the senses. It will probably be an object used to contain a description of a form, such as a book or the acoustic waves of a conversation. Any object that is not purely chaotic will have some level of form. |

|

Essence |

These are the attributes of an individual object that make it what it is. We can express these as descriptions of the object. Essence also applies to forms, and can be thought of in computational terms as metadata. The tree may be 10 meters tall or the chair may have armrests. |

|

Precept |

This is the image created in the mind by the senses of the object when it is encountered. It may be limited in quality by the senses, but is usually sufficient to classify the object as a chair or tree or whatever. It is important to note that a precept is active – it only exists as a precept while the object is being observed. |

|

Phantasm |

This is the mental image created of the perceived object by the imagination. The phantasm represents Form but since it consists of thought, it does not have Substance in itself. Therefore, the phantasm allows the object to be manipulated, copied, modified, and so on, literally at will. |

|

Concept |

This is the abstraction of the object in the mind that recognizes the essence of the object.So far, we have described the process for analyzing a single object. As the concept of this object is added to the mental library of concepts of other objects, both similar and dissimilar to the one being observed, we begin to form the basis of both language and thought. |

|

Species |

A class made up of multiple individuals with the same specific essence. All trees that are blackjack pine, for example. |

|

Genus |

A wider class of two or more species. All trees native to the temperate climate. The process of grouping individuals with shared attributes and dividing them by distinct attributes is called Taxonomy. |

|

Aggregate |

A group consisting of two or more individuals. They may or may not be the same species or genus. In fact, they may not share any attribute other than belonging to a given aggregate, such as objects in a room, or things observed by a specific person over a twelve hour period. |

|

Individual |

A single object. |

The mind may then learn of the world directly by comparing the essence, the attributes, of different objects and classifying each individual by species, genus, and aggregates. Language allows for both specific names for individual objects and general names for species based on attribute names that apply to essence. This language leads to Symbolism – the ability to represent not only objects, but the essence of objects, individuals, species, and aggregates as abstractions along with the concept of the objects themselves.

We have a natural mental scale to the naming of objects. We do not generally name specific blades of grass or rocks unless we are studying them in depth. Scientists working with Mars probes often come up with names for specific rocks in an image so they can discuss them as they decide where the rover is to drive next or what data they got back when drilling into a specific site. With symbolism, we can not only process the species, aggregates, concepts, and so on in our own mind, but we can communicate them to other human beings. We can encapsulate them in text which may be read hundreds or thousands of years later. We may even describe an object in sufficient detail that a robot can locate it within an aggregate, such as finding a part in a bin or a bar code on a wall of boxes.

Another power of symbolic classification and labeling, known as language, is that we can describe objects that do not exist at all, such as a unicorn, a planet orbiting between Earth and Venus, or a fictional character. We can Create concepts that do not currently exist by arranging the symbols into logical constructions that clearly articulate a new concept. We can also describe things using symbols that are entirely without substance, such as pure math.

The process of Invention, therefore, is essentially the mirror image of perception and analysis. We learn enough about the objects in the world that we have a vocabulary of symbols and a taxonomy of examples. We can then arrange, purely in forms within our minds, the symbols, attributes, and so on in the virtual workshop of the imagination. We can conceive of a car that has the attribute of exceeding the speed of sound. We can then use attributes from the species “things that exceed the speed of sound” (jet engines, rockets, etc.) and combine them symbolically with the concept of a “car” (four wheels, does not leave the ground, steering wheel, driver, and so on). We can then add things that are not part of either group, but are analogous and fulfill the same function. Cars like this require wheels made of aerospace-grade metals, which have no practical application otherwise. They must be crafted to the task at hand. However, they share the attributes, are part of the species, of the symbol we call a “wheel” in that they are round objects on an axle that support a ground vehicle. We have now expanded the genus of “wheel” to include these new species in the taxonomy tree. We may even find a practical application for them in a high speed train or centrifugal piece of industrial equipment.

We can then use this level of abstraction, the symbolic language in words, numbers, drawings – and use it to communicate to other humans and to computers needed in the design process. We can classify the parts and provide attributes of strength, weight, and so on. We can then use taxonomy to determine which parts exist (can be ordered) and which parts must be fabricated in a workshop. If we determine the attributes of a part are beyond the budget of the project, or cannot be fabricated with available components, budgets, or technology, we can scale the project back or cancel it altogether. But symbolic logic is of value to a social species such as humanity. We may not be able to fabricate a car that can go four times the speed of sound, but we can write a story about what it would be like to drive such a vehicle. We can also come up with a fictional design that allows the observer, the audience, to also imagine such a car in detail. We can come up with dozens of such designs in an afternoon on a pad of paper, expressed in the same symbolic language of sketches, captions, and other tools of the imagination. We can simulate driving such a vehicle in a short movie. That movie may inspire someone in a future generation to revisit the idea. If the technology exists in the taxonomy, it may happen in substance as well as form.

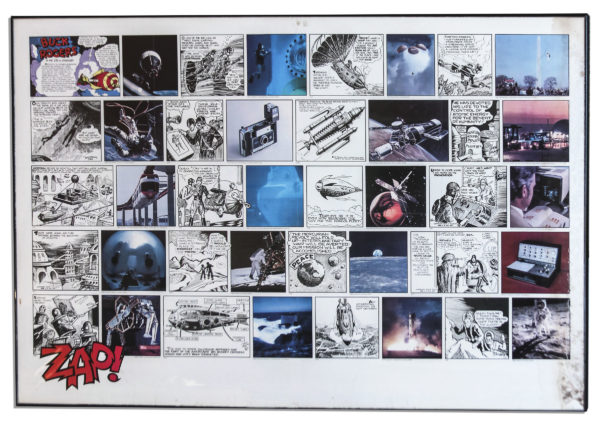

We will discuss the attribute of time and invention later in this series.It already happened with crewed rockets and space stations, which were predicted in science fiction long before they existed. I have a poster on my wall from the estate of Ray Bradbury. It contains, without comment, a series of cells from the old Buck Rogers cartoon strip from 1929-1946, followed by photos of the technology discussed in that cell as it existed in the early 1970’s. The cell/photo combinations describe a pair of spacecraft in orbit together, a scuba dive, a space capsule returning from space under parachutes, a jet pack, a spacewalk, an instant camera, a space station, a nuclear power plant, a monorail train, a personal submarine, a Mars probe, a video phone, an undersea base, a moonwalk, a view of Earth and the moon together from space, a lie detector, a walking industrial-sized robot, a nuclear submarine, a moon rocket, and another moonwalk.“The human intellect conceives and constructs the works of civilization.” And if they can’t build them in metal, they will draw them in ink for future generations.